The North Philadelphia home where I grew up — 2531 North 26th Street — was full of life and love. That’s because of my parents, Thomas Meredith Willis and Ruth Ellen Holman Willis.

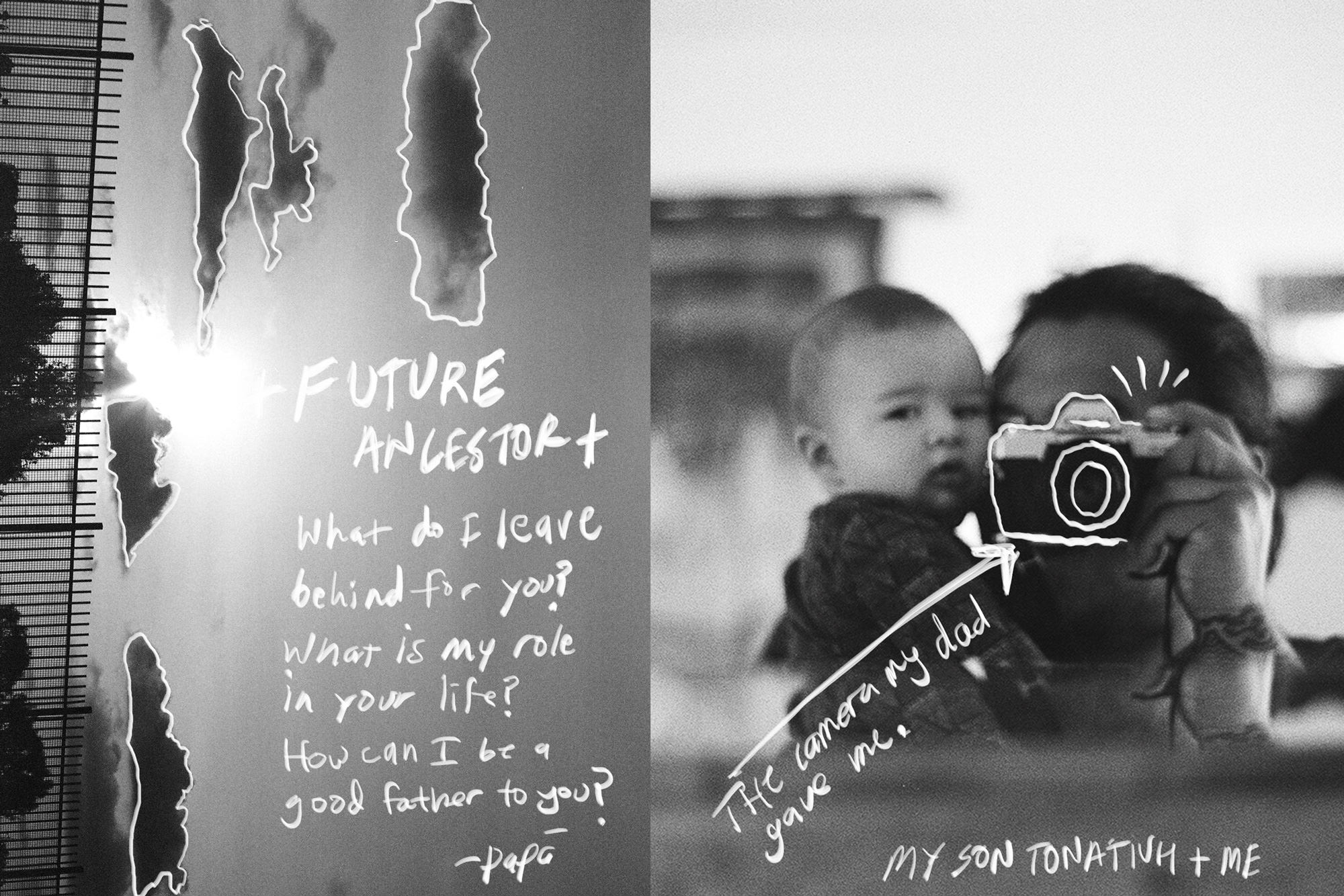

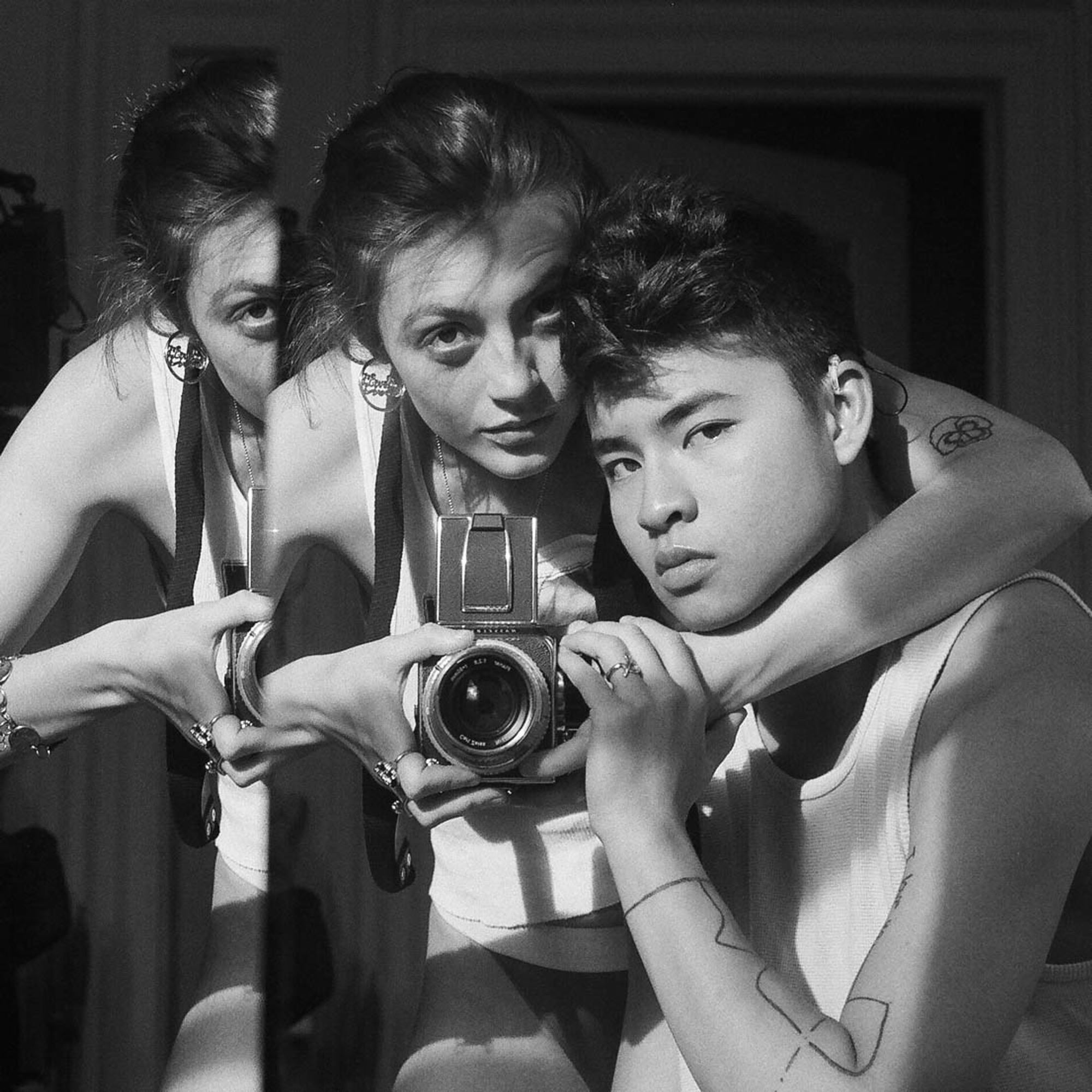

My dad worked as a police officer in Philadelphia and owned a grocery store and redesigned homes in the neighborhood. An avid reader and serious amateur photographer, he encouraged me to use his camera to make family photographs. My mom ran her beauty shop in our home in the upstairs “kitchen,” where women and girls visited every day except Sundays and Mondays to prepare for work/cultural/spiritual life. I recall sitting in my mom’s shop as early as age 7, reading books and magazines and listening to the women talk for hours — church and clubwomen, singers and housewives, domestic workers and teachers, aunts and cousins. It was a safe space to just “be.”

We were a close-knit family. My mom had 13 brothers and sisters, ten aunts and uncles, her parents, and grandparents. My dad had nine brothers and sisters. I had two sisters and more than 50 first cousins. We shared recipes and stories throughout our lifetime.